Originally Posted by

plug drugs

Page protected with pending changes level 1

Dunning–Kruger effect

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Dunning-Kruger)

Changes must be reviewed before being displayed on this page.show/hide details

Psychology

The Greek letter 'psi', a symbol for psychology

Outline History Subfields

Basic types

Abnormal Biological Cognitive Comparative Cross-cultural Cultural Differential Developmental Evolutionary Experimental Mathematical Neuropsychology Personality Positive Quantitative Social

Applied psychology

Applied behavior analysis Clinical Community Consumer Counseling Educational Environmental Ergonomics Forensic Health Humanistic Industrial and organizational Interpretive Legal Medical Military Music Occupational health Political Religion School Sport Traffic

Lists

Disciplines Organizations Psychologists Psychotherapies Publications Research methods Theories Timeline Topics

Portal icon Psychology portal

v t e

The Dunning–Kruger effect is a cognitive bias wherein relatively unskilled individuals suffer from illusory superiority, mistakenly assessing their ability to be much higher than is accurate. Dunning and Kruger attributed the bias to the metacognitive inability of the unskilled to recognize their own ineptitude and evaluate their own ability accurately. Their research also suggests that conversely, highly skilled individuals may underestimate their relative competence, erroneously assuming that tasks that are easy for them also are easy for others.[1] The bias was first experimentally observed by David Dunning and Justin Kruger of Cornell University in 1999.

Dunning and Kruger have postulated that the effect is the result of internal illusion in the unskilled, and external misperception in the skilled: "The miscalibration of the incompetent stems from an error about the self, whereas the miscalibration of the highly competent stems from an error about others."[1]

Contents [hide]

1 Original study

2 Supporting studies

3 Historical antecedents

4 Award

5 See also

6 References

7 Further reading

Original study[edit]

The phenomenon was first tested in a series of experiments during 1999 by David Dunning and Justin Kruger of the department of psychology at Cornell University.[1][2] The study was inspired by the case of McArthur Wheeler, a man who robbed two banks after covering his face with lemon juice in the mistaken belief that, because lemon juice is usable as invisible ink, it would prevent his face from being recorded on surveillance cameras.[3] The authors noted that earlier studies suggested that ignorance of standards of performance lies behind a great deal of incorrect self-assessment of competence. This pattern was seen in studies of skills as diverse as reading comprehension, operating a motor vehicle, and playing games such as chess or tennis.

Dunning and Kruger proposed that, for a given skill, incompetent people will:[4]

fail to recognize their own lack of skill

fail to recognize genuine skill in others

fail to recognize the extent of their inadequacy

recognize and acknowledge their own lack of skill, after they are exposed to training for that skill

Dunning has since drawn an analogy – "the anosognosia of everyday life"[5][6] – with a condition in which a person who suffers a physical disability because of brain injury seems unaware of, or denies the existence of, the disability, even for dramatic impairments such as blindness or paralysis: "If you're incompetent, you can’t know you’re incompetent.… [T]he skills you need to produce a right answer are exactly the skills you need to recognize what a right answer is."[5]

Supporting studies[edit]

Dunning and Kruger set out to test these hypotheses on Cornell undergraduates in psychology courses. In a series of studies, they examined subject self-assessment of logical reasoning skills, grammatical skills, and humor. After being shown their test scores, the subjects were asked to estimate their own rank. The competent group estimated their rank accurately, while the incompetent group overestimated theirs. As Dunning and Kruger noted:

Across four studies, the authors found that participants scoring in the bottom quartile on tests of humor, grammar, and logic grossly overestimated their test performance and ability. Although test scores put them in the 12th percentile, they estimated themselves to be in the 62nd.[1]

Meanwhile, subjects with true ability tended to underestimate their relative competence. Roughly, participants who found tasks to be easy, erroneously presumed to some extent, that the tasks also must be easy for others.[1]

A follow-up study, reported in the same paper, suggests that grossly incompetent students improved their ability to estimate their rank after minimal tutoring in the skills they had previously lacked, regardless of the negligible improvement gained in skills.[1]

In 2003, Dunning and Joyce Ehrlinger, also of Cornell University, published a study that detailed a shift in people's views of themselves when influenced by external cues. Participants in the study, Cornell University undergraduates, were given tests of their knowledge of geography. Some of the tests were intended to affect their self-views positively, some negatively. They were then asked to rate their performance. Those given the positive tests reported significantly better performance than those given the negative.[7]

Daniel Ames and Lara Kammrath extended this work to sensitivity to others and subject perception of how sensitive they were.[8]

Research conducted by Burson et al. (2006) set out to test one of the core hypotheses put forth by Kruger and Muller in their paper "Unskilled, unaware, or both? The better-than-average heuristic and statistical regression predict errors in estimates of own performance", "that people at all performance levels are equally poor at estimating their relative performance".[9] To test this hypothesis, the authors investigated three different studies, which all manipulated the "perceived difficulty of the tasks and hence participants’ beliefs about their relative standing".[9] The authors found that when researchers presented subjects with moderately difficult tasks, the best and the worst performers varied little in their ability to accurately predict their performance. Additionally, they found that with more difficult tasks, the best performers were less accurate in predicting their performance than the worst performers. The authors concluded that these findings suggest that "judges at all skill levels are subject to similar degrees of error".[9]

Ehrlinger et al. (2008) made an attempt to test alternative explanations, but came to conclusions that were qualitatively similar to the original work. The paper concludes that the root cause is that, in contrast to high performers, "poor performers do not learn from feedback suggesting a need to improve".[10]

Studies on the Dunning–Kruger effect tend to focus on American test subjects. A number of studies on East Asian subjects suggest that different social forces are at play in different cultures. For example East Asians tend to underestimate their abilities and see underachievement as a chance to improve themselves and to get along with others.[11]

Historical antecedents[edit]

Although the Dunning–Kruger effect was formulated in 1999, Dunning and Kruger have noted earlier observations along similar lines by philosophers and scientists, including Confucius ("Real knowledge is to know the extent of one's ignorance"),[2] Bertrand Russell ("One of the painful things about our time is that those who feel certainty are stupid, and those with any imagination and understanding are filled with doubt and indecision"),[10] and Charles Darwin, whom they quoted in their original paper ("Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge").[1]

Geraint Fuller, commenting on the paper, noted that Shakespeare expressed a similar observation in As You Like It ("The Foole doth thinke he is wise, but the wiseman knowes himselfe to be a Foole" (V.i)).[12]

Award[edit]

Dunning and Kruger were awarded the 2000 satirical Ig Nobel Prize in psychology "for their modest report, 'Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments'".[13]

See also[edit]

Curse of knowledge

Four stages of competence

Hanlon's razor

Impostor syndrome

Not even wrong

Overconfidence effect

Self-efficacy

Self-serving bias

Superiority complex

References[edit]

^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Kruger, Justin; Dunning, David (1999). "Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77 (6): 1121–34. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121. PMID 10626367. CiteSeerX: 10.1.1.64.2655.

^ Jump up to: a b Dunning, David; Johnson, Kerri; Ehrlinger, Joyce; Kruger, Justin (2003). "Why people fail to recognize their own incompetence" (PDF). Current Directions in Psychological Science 12 (3): 83–87. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.01235. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

Jump up ^ "Why Losers Have Delusions of Grandeur". New York Post. 23 May 2010. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

Jump up ^ Lee, Chris (2012-05-25). "Revisiting why incompetents think they’re awesome". Arstechnica.com. p. 3. Retrieved 2014-01-11.

^ Jump up to: a b Morris, Errol (20 June 2010). "The Anosognosic's Dilemma: Something's Wrong but You'll Never Know What It Is (Part 1)". New York Times. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

Jump up ^ Dunning, David (2005). Self-Insight: Roadblocks and Detours on the Path to Knowing Thyself (Essays in Social Psychology). Psychology Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 1-84169-074-0.

Jump up ^ Ehrlinger, Joyce; Dunning, David (January 2003). "How Chronic Self-Views Influence (and Potentially Mislead) Estimates of Performance". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (American Psychological Association) 84 (1): 5–17. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.5. PMID 12518967.

Jump up ^ Ames, Daniel R.; Kammrath, Lara K. (September 2004). "Mind-Reading and Metacognition: Narcissism, not Actual Competence, Predicts Self-Estimated Ability" (PDF). Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 28 (3): 187–209. doi:10.1023/B:JONB.0000039649.20015.0e. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

^ Jump up to: a b c Burson, K.; Larrick, R.; Klayman, J. (2006). "Skilled or unskilled, but still unaware of it: how perceptions of difficulty drive miscalibration in relative comparisons" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (1): 5. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.60. PMID 16448310. hdl:2027.42/39168.

^ Jump up to: a b Ehrlinger, Joyce; Johnson, Kerri; Banner, Matthew; Dunning, David; Kruger, Justin (2008). "Why the unskilled are unaware: Further explorations of (absent) self-insight among the incompetent" (PDF). Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 105 (1): 98–121. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2007.05.002. PMC 2702783. PMID 19568317.

Jump up ^ DeAngelis, Tori (Feb 2003). "Why we overestimate our competence". Monitor on Psychology (American Psychological Association) 34 (2): 60. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

Jump up ^ Fuller, Geraint (2011). "Ignorant of ignorance?". Practical Neurology 11 (6): 365. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2011-000117. PMID 22100949.

Jump up ^ "Ig Nobel Past Winners". Retrieved 7 March 2011.

Further reading[edit]

Dunning, David (27 October 2014). "We Are All Confident Idiots". Pacific Standard (Miller-McCune Center for Research, Media, and Public Policy). Retrieved 28 October 2014. A popular commentary by David Dunning, with links to other articles, about the research program on how human beings evaluate their own knowledge and competence.

Categories: Social science methodologySocial psychologyCognitive biasesIncompetence

Navigation menu

Create accountNot logged inTalkContributionsLog inArticleTalkReadEditView history

Main page

Contents

Featured content

Current events

Random article

Donate to Wikipedia

Wikipedia store

Interaction

Help

About Wikipedia

Community portal

Recent changes

Contact page

Tools

What links here

Related changes

Upload file

Special pages

Permanent link

Page information

Wikidata item

Cite this page

Print/export

Create a book

Download as PDF

Printable version

Languages

Afrikaans

العربية

Български

Brezhoneg

Català

Čeština

Dansk

Deutsch

Eesti

Español

فارسی

Français

한국어

Hrvatski

Bahasa Indonesia

Italiano

עברית

ქართული

Magyar

Nederlands

日本語

Norsk bokmål

Oʻzbekcha/ўзбекча

Polski

Português

Română

Русский

Simple English

Slovenčina

Slovenščina

Српски / srpski

Suomi

Svenska

தமிழ்

Türkçe

Українська

中文

Edit links

This page was last modified on 21 October 2015, at 06:51.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

Privacy policyAbout WikipediaDisclaimersContact WikipediaDevelopersMobile viewWikimedia Foundation Powered by MediaWiki

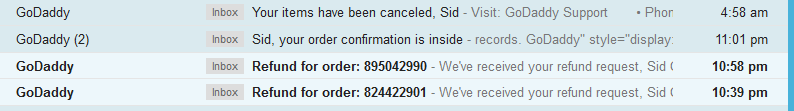

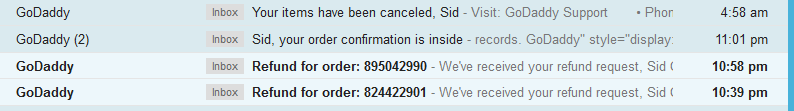

L, 900 dollars to transfer that to the new account 100 bucks per domain. so i told him, fine, don't transfer it, i'll make backups of all of it and put it back on myself and he said, no you don't understand there are 9 domains and they all have to be set up and i said, guy i just explained to you all this shit about the zone files and all the stuff we'd just been talking about and i said, yeah again, the databases what about them? will all that get migrated and will i have to set up everything again because the fqdns and the ip addresses will be diff and to register the databases properly with the accounts built in, they would have to be manually transfered - now he had said previously that all of it would be done seamlessly but now he said, no if you had ONE database and ONE domain then it was all inclusive, but you ahve all of these databases and 9 domains. so then i knew this guy was a choth and i just said, fine i will deal with it and get back to you if and when i want to transfer.

Originally Posted by plug drugs

Originally Posted by plug drugs

Originally Posted by plug drugs

Originally Posted by plug drugs

but dont take it up with me, take it up with jesus

but dont take it up with me, take it up with jesus